Bone Bank Archaeological Research

Posey County, Indiana

Rescue Excavations at the Bone Bank Archaeological Site in Southwestern Indiana

Introduction

Introduction

Indiana's First Archaeological Excavation

Indiana's First Archaeological Excavation

Survey and Testing

Survey and Testing

Significance

Significance

Project Goals

Project Goals

Research Stages

Research Stages

Expected Results

Expected Results

Bone Bank in 2000

Bone Bank in 2000

Planning for 2001

Planning for 2001

Current Work

Current Work

In the News

In the News

Fall 2001 Lecture

Fall 2001 Lecture

References

References

Geomorphological History

Geomorphological History

Links

Links

Maps

Maps

INDIANA'S FIRST ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS

Bone Bank site is one of the first archaeological sites ever to be reported in the state of Indiana. The excavations there in 1828 make Bone Bank the first

site in the state to be excavated, and one of the earliest in the United States 9THomas Jefferson's 1781 excavation of a burial mound in Virginia was the first).

In 1807, Arthur Henrie wrote about the materials he found eroding from the river during his initial land survey of Posey County for the U.S. Government Land Office.

Henrie's survey accurately recorded the location of Bone Bank. The river bank in 1807 was located more than 200 feet further west.

The 1828 excavations were carried out by the French naturalist and artist Charles Alexander Lesueur, who resided in New Harmony (Bonnemains 1984; Elliott and Johansen 1999; Hamy 1968).

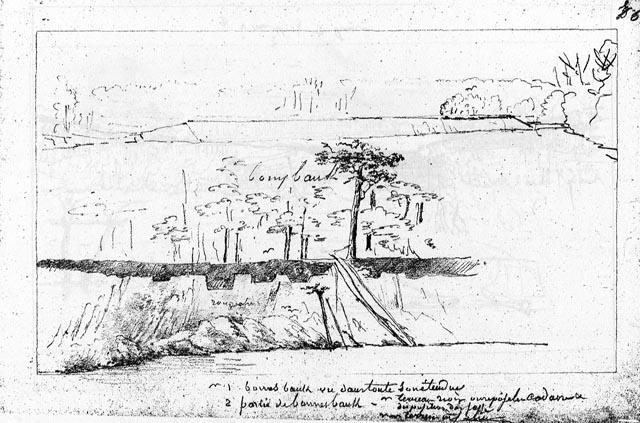

While en route to New Orleans by boat, Lesueur stopped at Bone Bank where he made excavations and sketched both the site layout and a series of artifacts.

Years later, Lesueur took the site collections and drawings with him when he returned to Le Havre, France. Only his drawings have survived to the present era (Bonnemains 1984),

but these tell us about some of the artifacts he found and the kinds of interpretations he made. Most importantly, they tell us about the size of the village site before its present

much-reduced state, and about features such as deep pits (house basins) and cemeteries which are no longer evident.

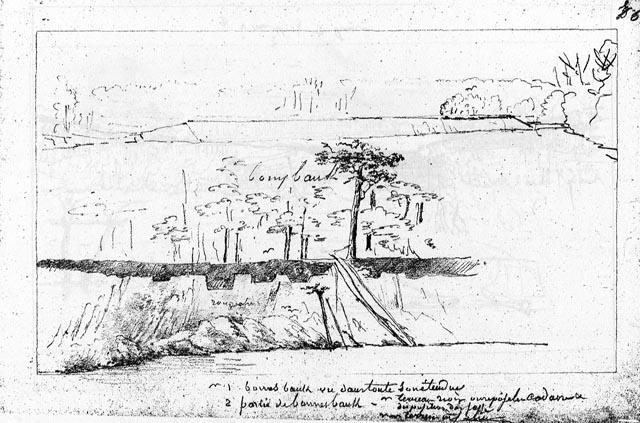

C.-A. Lesueur's 1828 drawing (no. 41193) of the river bank at Bone Bank, showing huge basins of midden deposits.

C.-A. Lesueur's drawing (no. 41194) of the profile of the Bone Bank site and bones that have eroded from a higher level, captioned

"Arbre renversé avec un squelette dans ses racines - os perçant le bank - Bonnes Bank (Bonnemains 1984: Plate 149). The profile of the site looks much the same today,

except that the bank is located hundreds of meters to the east, and human bones are no longer evident.

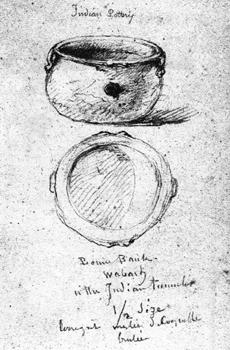

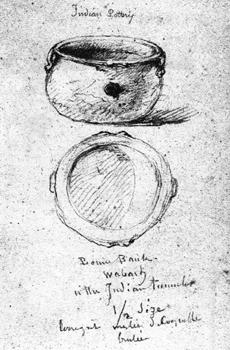

Lesueur's captions for a number of his illustrations demonstrate his thinking about artifacts and archaeological sites. For example, on drawing #41197, he wrote:

"Indian pottery – Bonne Bank –Wabash – in the Indian tumulus – ½ size – ... mêlées de coquilles brûlées...". ...Bonnemains 1984:44).

The attribution of the Bone Bank site and artifacts (pottery with burned shell temper) to a Native American origin was far ahead of the times.

Other writers in the mid-late 1800s were caught up in the fanciful and racist speculations about an exotic mythical race of "Moundbuilders" which captured the fancy

of most people interested in archaeology.

Translations of Lesueur’s account of his work indicate that the site extended over a distance of about 800 m.

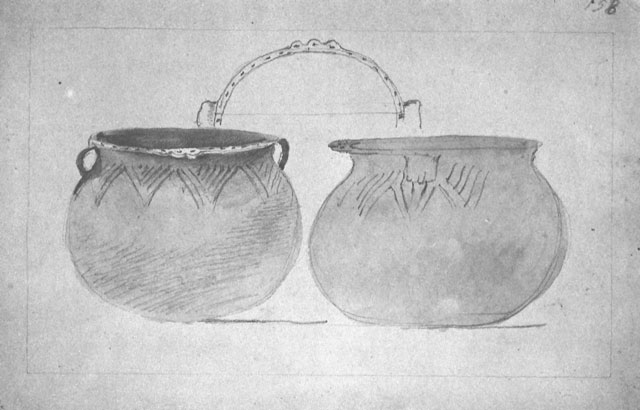

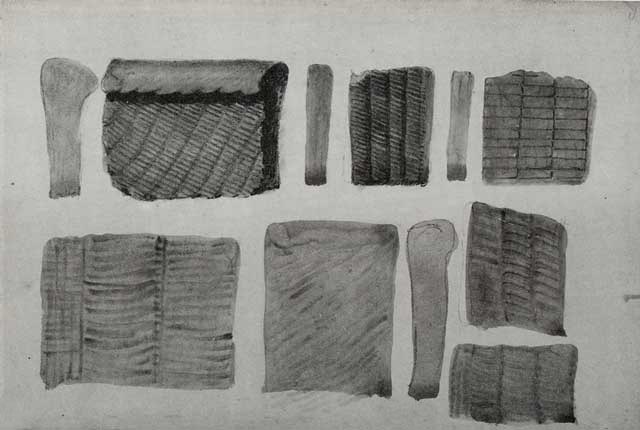

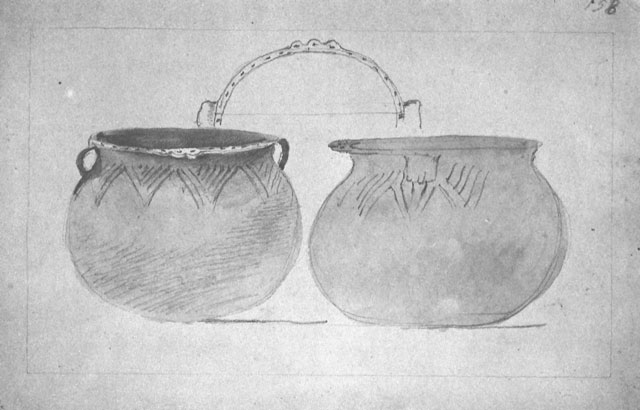

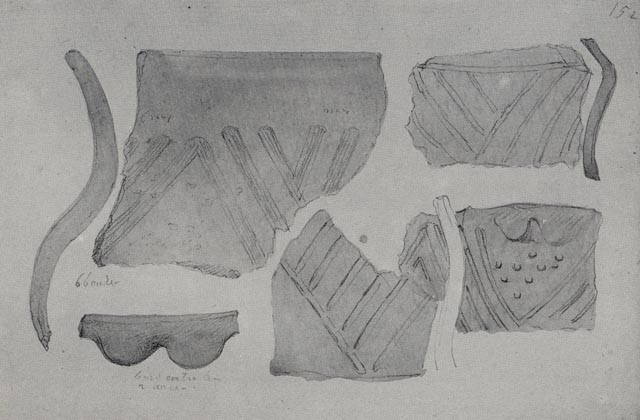

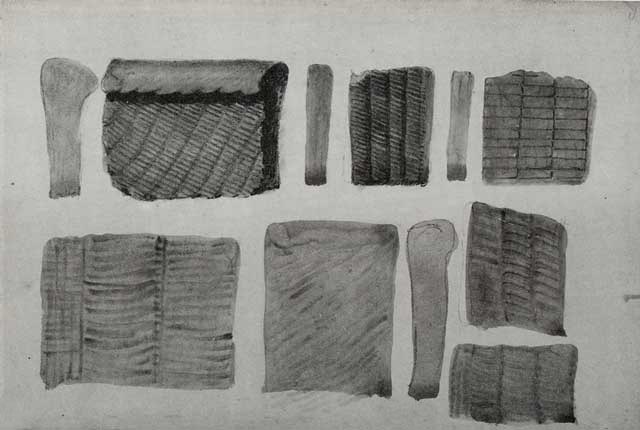

While jars, bowls, and bottles with plain surfaces are the most common types of Mississippian pottery found at Bone Bank, Lesueur focused his illustrations on decorated vessels.

Lesueur's drawing (41207) shows to side views of a jar with incised decorations typical of Caborn-Welborn Decorated.

The vessel has a pair of opposed strap handles, as well as pair of opposed nodes (with three nodes per set).

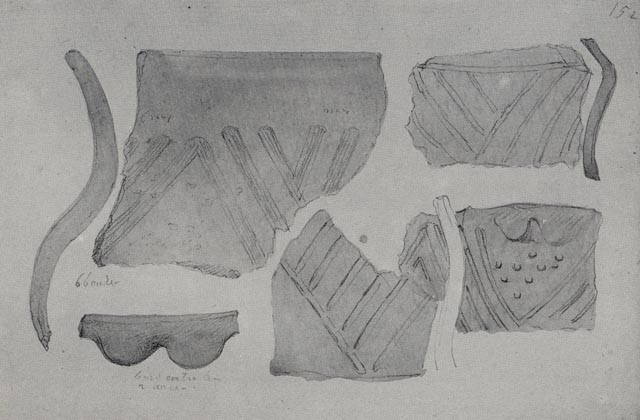

Other fragments of Caborn-Welborn Decorated jars (Lesueur 41201) show both incised and punctate motifs.

This incised jar design (Lesueur 41205) is a variety of Caborn-Welborn Decorated that is very similar to Oneota jar motifs found in regions to the north

and east of the mouth of the Wabash. Note the nested circle and the loop handle. Oneota motifs occur as small per cent of the decorated ceramics at many Caborn-Welborn sites.

The more typical jars from Bone Bank have plain surfaces and loop or strap handles (Lesueur 41202).

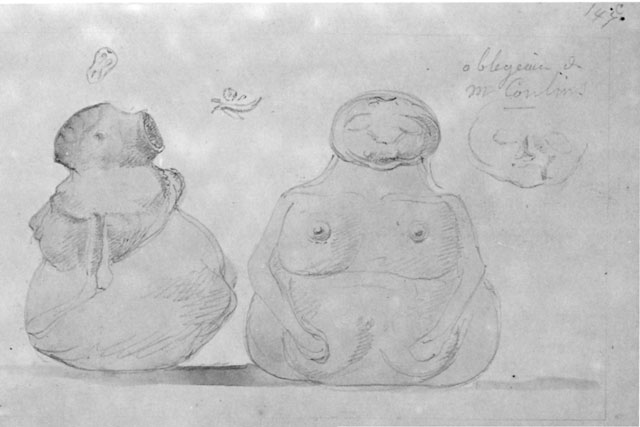

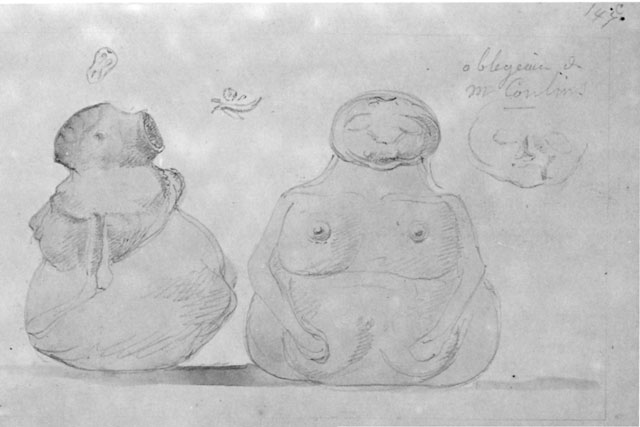

Lesueur's illustration (41211) of a human female effigy bottle shows a type of vessel found at most Caborn-Welborn sites.

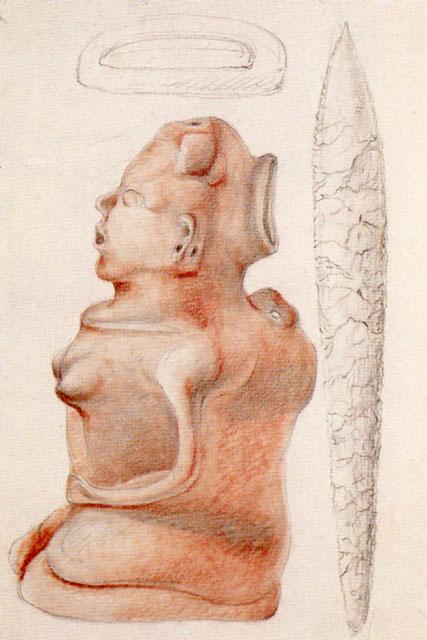

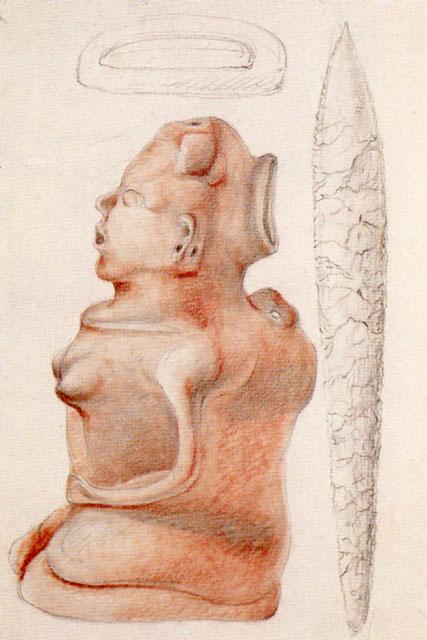

The human effigy bottle in Lesueur's drawing 41212 shows pronounced collar bones. Similar figures, also with pronounced collar bones are found in the Mississippi River Valley of Missouri, Arkansas, and Tennessee. The object on the right depicts a large chipped flint knife blade. The object at the top is unknown.

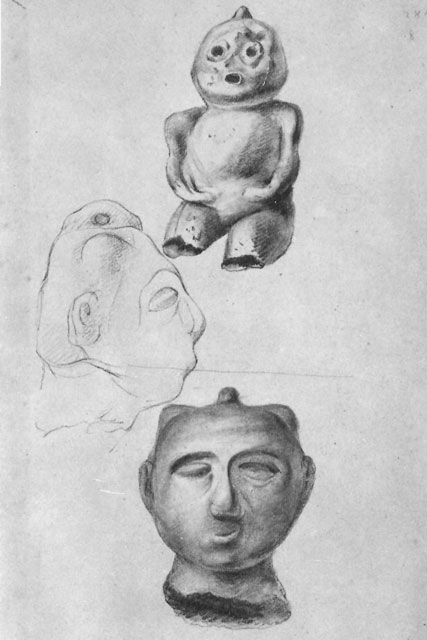

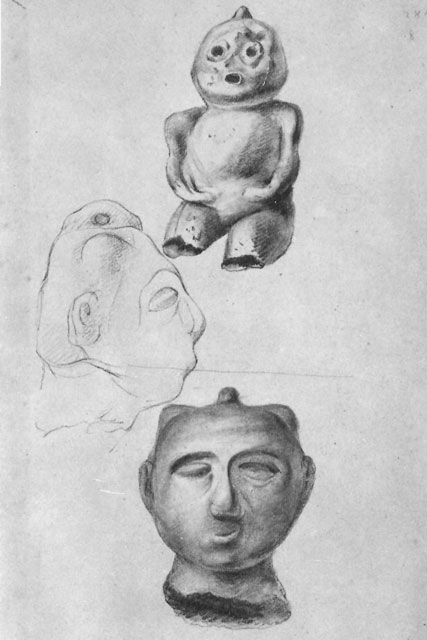

Other examples of the human form at Bone Bank are a ceramic figurine and an effigy head attachments to a bowl (Lesueur 41210).

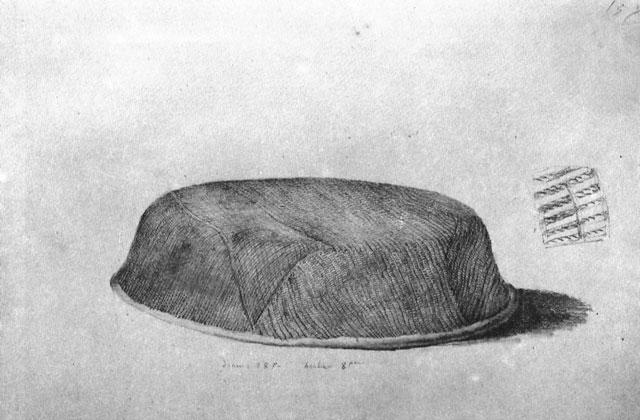

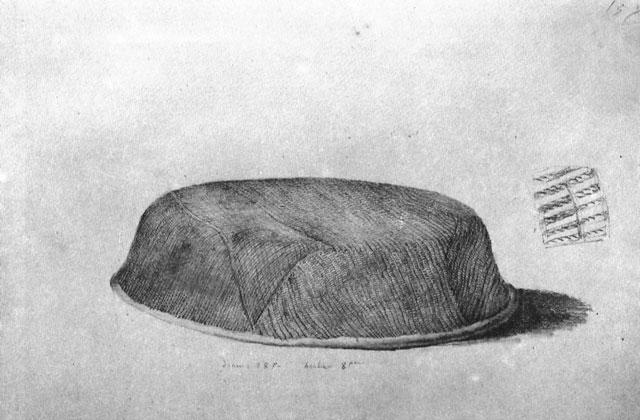

A complete vessel from Bone Bank is a fabric impressed bowl that is unusual because it was complete. It is shown upside down to illustrate the impressions (Lesueur 41208). Archaeologists refer to these shallow wok-like bowls as "salt pans," because this type of vessel is common at saline springs used by Mississippian peoples. This type of bowl is also found at Mississippian villages located far from salt springs.

Lesueur's illustration (41200) of a variety of fabric impressed bowls. Pieces of fabric were probably used as part of the vessel-making process to line molds, rather than to decorate the bowls.

Later scientists, including state geologist E.T. Cox (1874), recognized that the site had become much diminished.

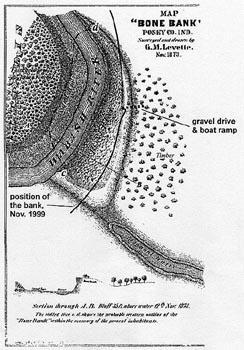

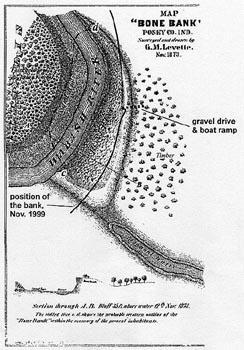

G. M. Levette's 1873 map and section of the Bone Bank site (from Cox 1874, frontispiece), modified (heavy line) to show the approximate position of the modern cutbank. Note the location on both Levette's map and section of a 19th century farmhouse.

The collecting and digging of artifacts from the eroding bank produced many exquisite pottery vessels, some of which were purchased by local collectors from Evansville. When the Heye Foundation acquired collections for the Museum of the American Indian in New York City, the Charles Artes collection from Bone Bank was purchased. A part of this collection – the more exotic specimens, including effigy vessels, stirrup spout bottles, compound vessels, as well as painted and modeled “head pots” (Hathcock 1976: Figs. 570, 582; Hathcock 1983; Figs. 20B, 20C) – has been exhibited. At present, the Museum of the American Indian is in the process of moving to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C

Head pot collected from the Bone Bank site (Museum of the American Indian). Archaeologists have recorded a complete head pot and several fragments of head pots at other Caborn-Welborn villages.

Because they cannot be associated or dated, the artifact collections that came from the uncontrolled digging tell us very little, but they do have aesthetic value. Some of the collected and reported artifacts – including chert hoes, marine shell, and copper – also hint at the long distance trade that the Bone Bank villagers participated in. The “head pots” and other highly decorated ceramic vessels represent styles not locally made in the Wabash or Ohio Valleys, but are typical of the lower Mississippi Valley (Pollack and Munson 1998). These vessels could have been traded from distant regions or were locally made copies of non-local styles.

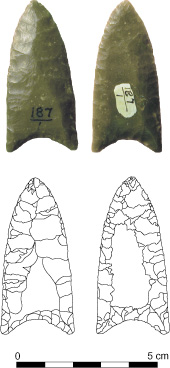

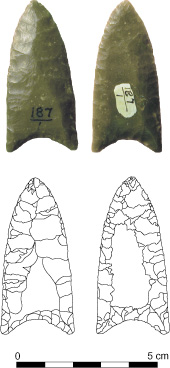

The discovery of a PaleoIndian Clovis spear point at Bone Bank was significant because the specimen was recorded as being found in situ -- in place -- in the riverbank, about 5 feet below surface. This discovery and report was made by Francis Vreeland in 1933.

This Clovis fluted point from Bone Bank is still the only in situ PaleoIndian artifact known in Indiana. The edges of the base and the lower portion of the sides were intentionally dulled by grinding. This prevented the lastings, which attached the point to the shoft of a spear, from being cut. The point is shorter that it was originally because the tip has abeen extensively resharpened. (Curated at the Glenn A. Black Laboratory of Archaeology, Indiana University.)

Following Lesueur and Cox, later writers and archaeologists, including Eli Lilly (1937), Adams (1949), and Henn (1971), all believed that Bone Bank had been essentially destroyed. Recent surveys and test excavations have demonstrated that while the cemeteries and house sites are indeed gone, significant archaeological deposits remain intact (Munson 1997, 2000).

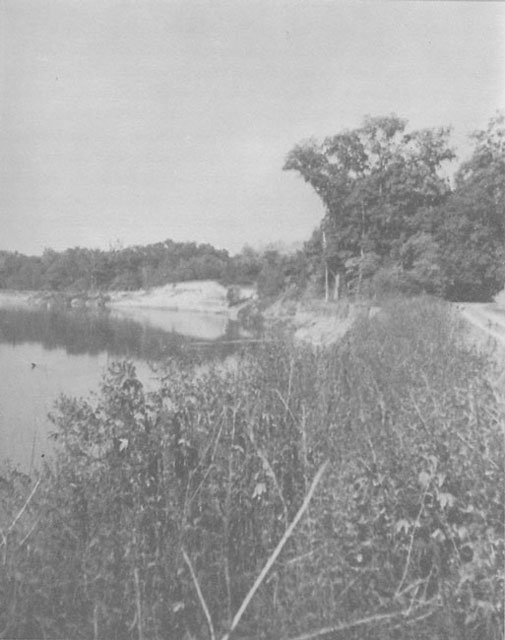

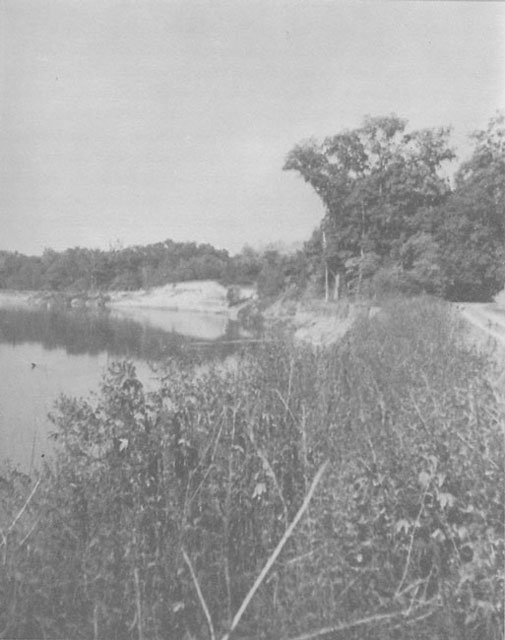

The Bone Bank site photographed in the early 1930s shows the exposed riverbank. The site looks much the same today, except that much of the high ground seen in the photo has been lost to erosion. (From Eli Lilly's "Prehistoric Antiquities of Indiana," 1937, Indiana Historical Society.)

Return to Top

Last updated on 3/26/2024

Send Comments to: munsonc@indiana.edu

Site sponsored by Indiana University

Introduction

Introduction

Indiana's First Archaeological Excavation

Indiana's First Archaeological Excavation

Survey and Testing

Survey and Testing

Significance

Significance

Project Goals

Project Goals

Research Stages

Research Stages

Expected Results

Expected Results

Bone Bank in 2000

Bone Bank in 2000

Planning for 2001

Planning for 2001

Current Work

Current Work

In the News

In the News

Fall 2001 Lecture

Fall 2001 Lecture

References

References

Geomorphological History

Geomorphological History

Links

Links

Maps

Maps